The moment of death is where Margaret Schwartz’s research begins.

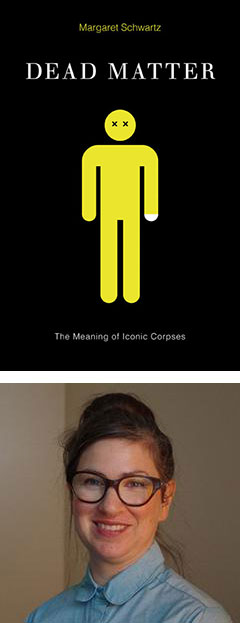

In her new book, Dead Matter: The Meaning of Iconic Corpses (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), Schwartz examines postmortem viewing practices, such as embalming, and the ritual and aesthetic roles that these play in mourning. She argues that the way we depict corpses—and which corpses we choose to depict—reveals certain truths about our conception of the human body.

“The book comes out of a very personal experience, which was seeing my father’s corpse when I was 15,” said Schwartz, PhD, an associate professor of communication and media studies.

“The book comes out of a very personal experience, which was seeing my father’s corpse when I was 15,” said Schwartz, PhD, an associate professor of communication and media studies.

“The difference between that moment—which was shocking enough—and the way he looked once he was embalmed and prepared—which was much worse, as I recall—sent me down this rabbit hole of wondering what kind of representational structures and techniques had intervened between the body at the moment of death and the body as it was then ‘presented’ for viewing and mourning.

“It also struck me that mourning is not something we as a culture do very well.”

Schwartz takes up the issue of postmortem photography, the aesthetic precursor to embalming in which bodies were photographed before burial. Photographers would pose the corpses so that they appeared relaxed and their faces happy, which provided grieving families with mementos of their loved ones at peace.

This serene look later translated to the embalming process, which preserves the body to allow mourners a service and final viewing. Faces receive cosmetic applications to give skin a more lifelike glow, and bodies are arranged to look at peace, as if merely asleep.

“Both photography and embalming create the experience of death and mourning as primarily visual,” Schwartz said. “It’s a denial of death and decomposition by working to restore the appearance of life.”

These visual mourning practices have social and political implications, creating what Schwartz calls a “body politic.” She cites an early English political concept that viewed the body of the king as having a dual existence: one that “ages, makes mistakes, dies,” she said, and the other, a “body politic,” which exists beyond the physical, transient body. After a king’s death, the body politic was ritually transferred from the physical body of the deceased king to the body of his successor.

Traces of this body politic still exist in our modern notions of death, Schwartz said. The death of a political leader or social figure prompts a loss beyond that of the individual.

“The body of the leader is both a personal and political entity. So, when Lincoln dies, we have a personal loss, for his family, but we also have a political situation,” Schwartz said.

“Tabloid bodies,” such as Princess Diana or Michael Jackson, and “martyred bodies,” such as Emmett Till and Hamsa al-Khateeb, also come to signify larger bodies—for instance, the plight of the marginalized or the continued value of deceased celebrities.

This move shifts our communal awareness from the deceased person to the larger body politic at work, and thus reinforces a denial of death. That focus, together with technologies and practices of mourning that work to cover up the decay of death, are partly what make us ineffectual mourners, Schwartz said.

“Death as an embodied experience has passed out of our awareness,” she said. “Accepting and understanding death and decomposition allows us to restore some dignity to the mourning process.”