In the past year, American women have experienced a new resurgence of female activism: From the January 2017 Women’s March to the sudden collective outcry of #MeToo to the historic number of women running for elected office.

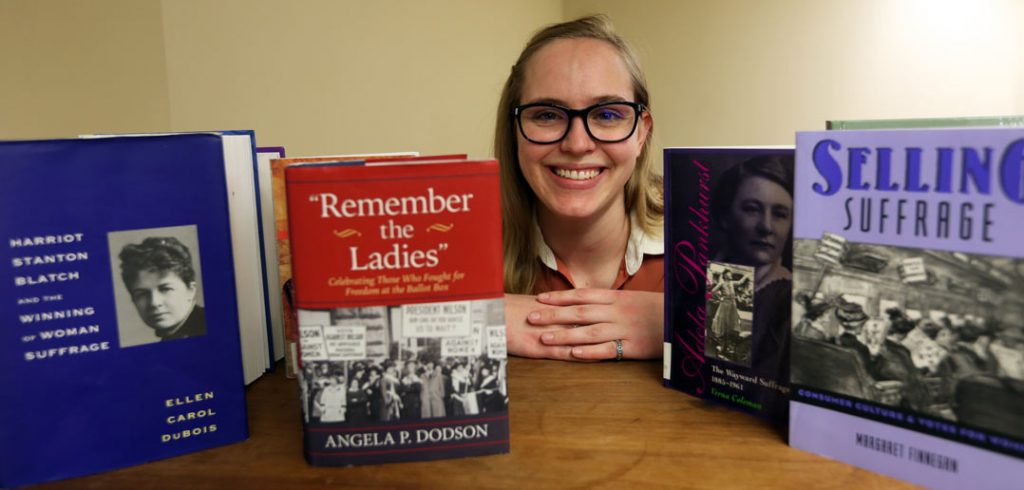

Graduate School of Arts and Sciences student Jordyn May is studying the necessary forerunner of this recent political activism: the women’s suffrage movement.

Graduate School of Arts and Sciences student Jordyn May is studying the necessary forerunner of this recent political activism: the women’s suffrage movement.

May, a first-year doctoral student in history, focuses her research on the visual culture of the suffrage movement from 1900 to 1920. Initially interested in the intersection between art and women’s rights, May was encouraged by her mentor, Kirsten Swinth, Ph.D., associate professor of history, to zero in on early women’s suffrage.

Because of Fordham’s location in the city, May chose New York as her geographic focus. Coincidentally, New York state also played a major role in the movement’s national success, she said.

Archival Treasures

“The campaign in New York became essential for the passage of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution, and was an amazing case study.” she said.

May has been conducting much of her archival research at the New York Public Library. The library collection has given her access to the papers and photos of organizations and individuals central to the suffrage movement in New York; these include the National American Woman Suffrage Association, the Empire State Campaign Committee, the New York State Woman Suffrage Party, and suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt.

May has been conducting much of her archival research at the New York Public Library. The library collection has given her access to the papers and photos of organizations and individuals central to the suffrage movement in New York; these include the National American Woman Suffrage Association, the Empire State Campaign Committee, the New York State Woman Suffrage Party, and suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt.

“New York City has been the most amazing thing for my research,” said May, who hails from California. “There are numerous archives within a subway ride from my apartment.”

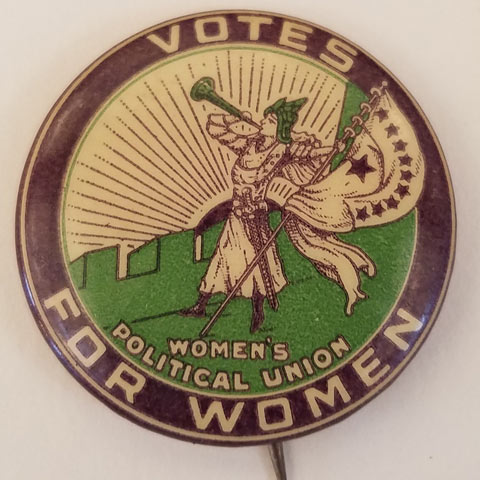

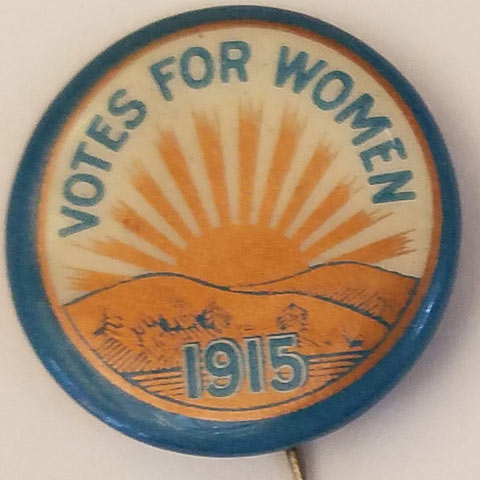

Through additional research at Smith College, May has collected hundreds of pamphlets, leaflets, buttons, banners, posters, political cartoons, and other visual propaganda used in the New York women’s suffrage campaign. She has gained an understanding of how leaders used visual propaganda to advance the movement.

“Suffrage propaganda sought to anger people by showing the injustice and oppression of women in society,” she said. “It aimed to reach empathetic supporters and followers of their cause, to pull on the patriotic feelings of Americans, and to soothe people’s concerns about what women would do with the vote.”

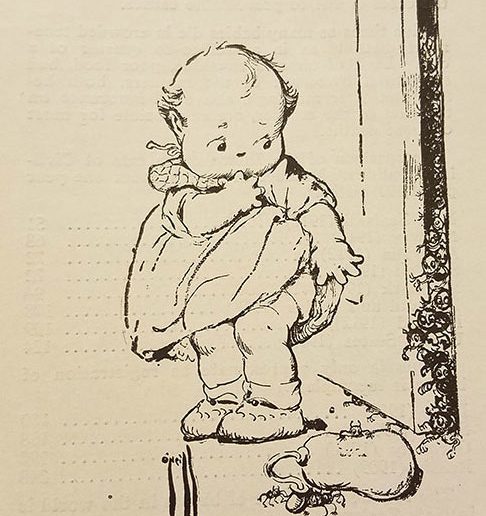

Women’s Suffrage and Better Babies

One propaganda pamphlet, called Better Babies, depicts an infant being attacked by germs; it was an attempt to suggest that America’s infant mortality rate would drop with women’s suffrage, said May. The caption reads “I wish my mother had a vote – to keep the germs away.”

She sees a parallel between how the suffragettes embraced new technological communication advancements after 1900 (such as movies and electric signage) and the catalyzing force of using social media in today’s women’s movements.

“Women are still fighting today for our equal rights and representation,” she said. “Before, suffragettes [were]on soap boxes talking; now they’re on Facebook and Twitter, making sure people know what events are happening. Parades for suffragettes were huge events—one attracted 45,000 marchers. It’s pretty great that [women’s marches are] still happening today. I am encouraged and inspired by these women who are speaking out, marching in the streets, and making a difference.”

In the spring, May plans to participate in a women’s suffrage symposium hosted by the Bronx Historical Society, where she will discuss her research.

For those looking to celebrate Women’s History Month in New York City, May suggests taking advantage of the Museum of the City of New York’s “Beyond Suffrage” exhibition or visiting the New York Historical Society’s Center for Women’s History.

—Rebecca Sinski, FCRH ’17