Fordham’s William Spain Seismic Observatory is celebrating its 100th anniversary.

Since 1924, Jesuits and their lay counterparts have been measuring earthquakes in this one-story Gothic structure, which currently stands next to Edwards Parade on the Rose Hill campus. Its equipment detects temblors around the world, including the 4.8 magnitude earthquake that rattled the area in April.

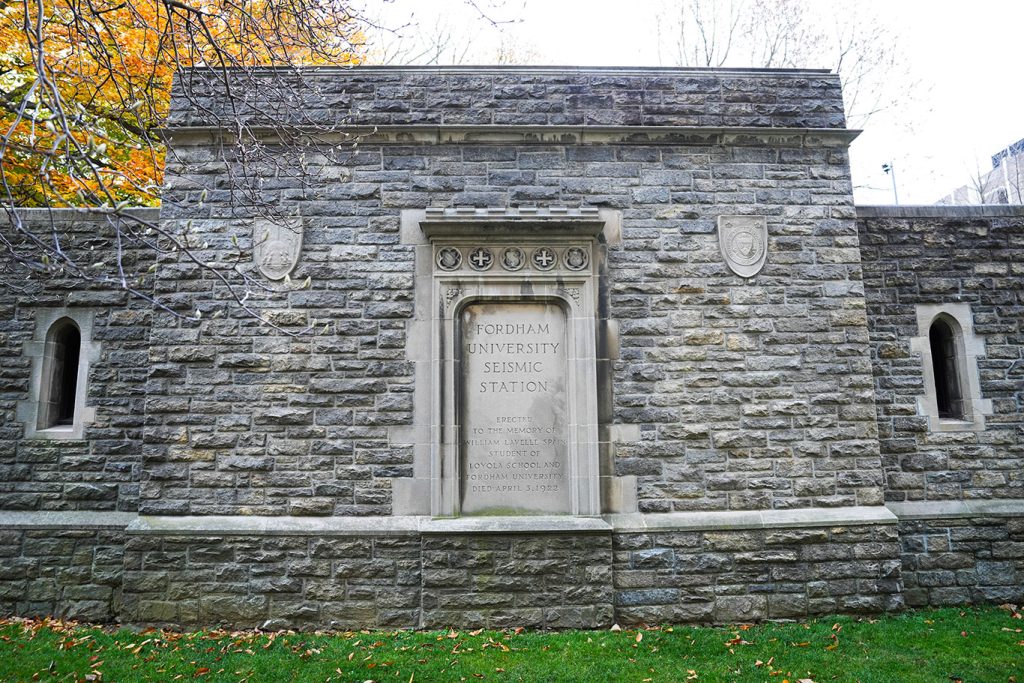

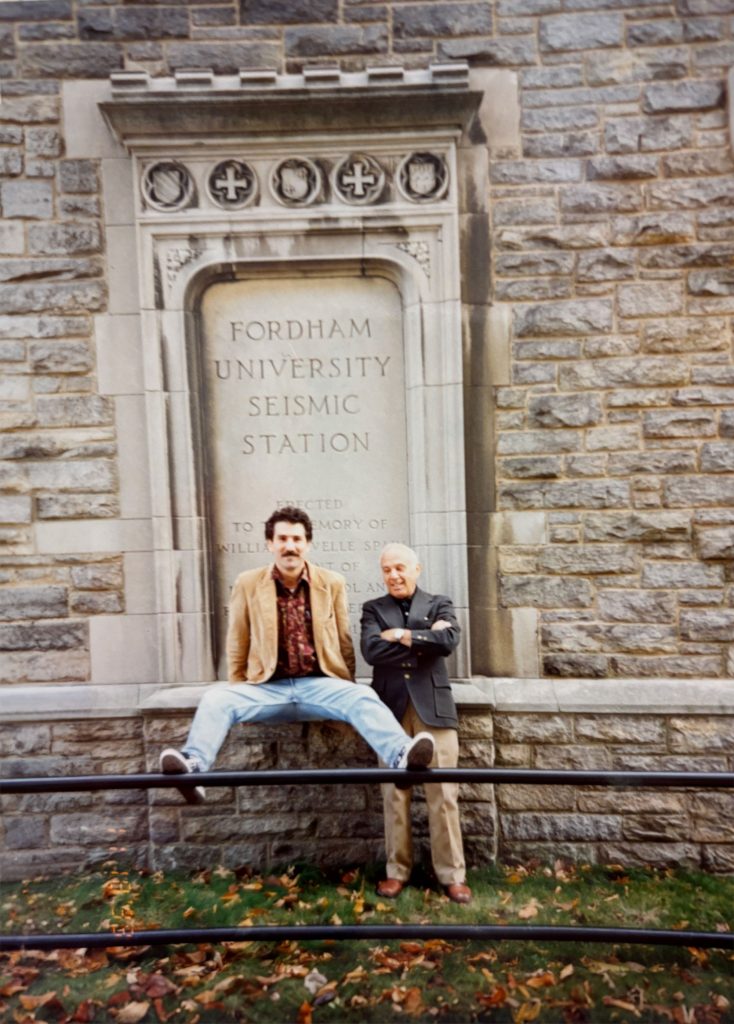

The observatory, which consists of an unassuming above-ground structure and a concrete vault 28 feet underground where the seismic instruments reside, is easy to miss. But it has played an important role in the advancement of seismology and physics over the years.

Stephen Holler, Ph.D., chair of Fordham’s physics department, who maintains the station, said it’s important to “keep an eye” on the planet and its rumblings.

“We’re always learning things about the Earth, and especially in the kind of high-density area that we’re in, it’s useful to monitor for earthquakes [and other tremors],” he said. “Maybe, in the event that something is happening or changing, we can potentially prepare for it.”

In the years that it has been operational, the station has recorded many earthquakes, including an 8.6 magnitude quake that struck Alaska in 1946 and a 7.7 magnitude quake that struck Taiwan in 1999. Holler is often called on by the media to discuss earthquakes when they strike the area.

Digging Deep

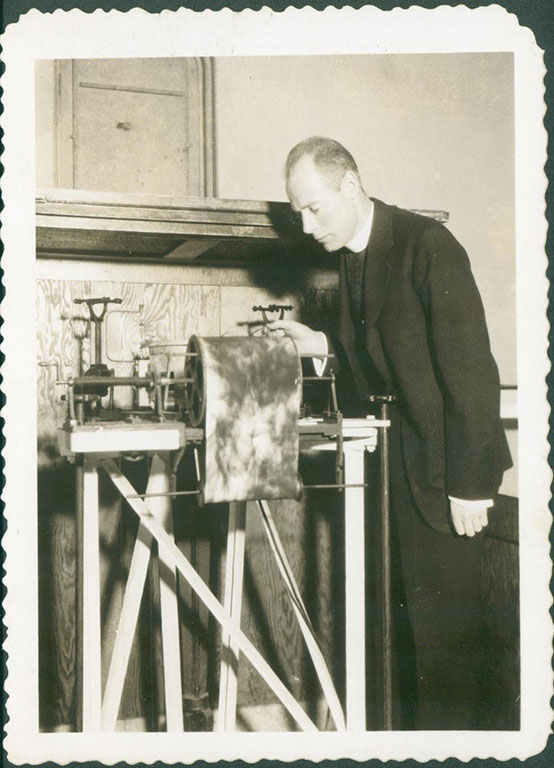

Fordham first got involved in seismology in 1910—along with nine other Jesuit colleges—through the Seismological Society of America, which had a Jesuit priest as one of its founding members. That year, a seismograph was installed in the basement of Cunniffe Hall. In 1920, Joseph J. Lynch, S.J., a physics instructor, took over the station.

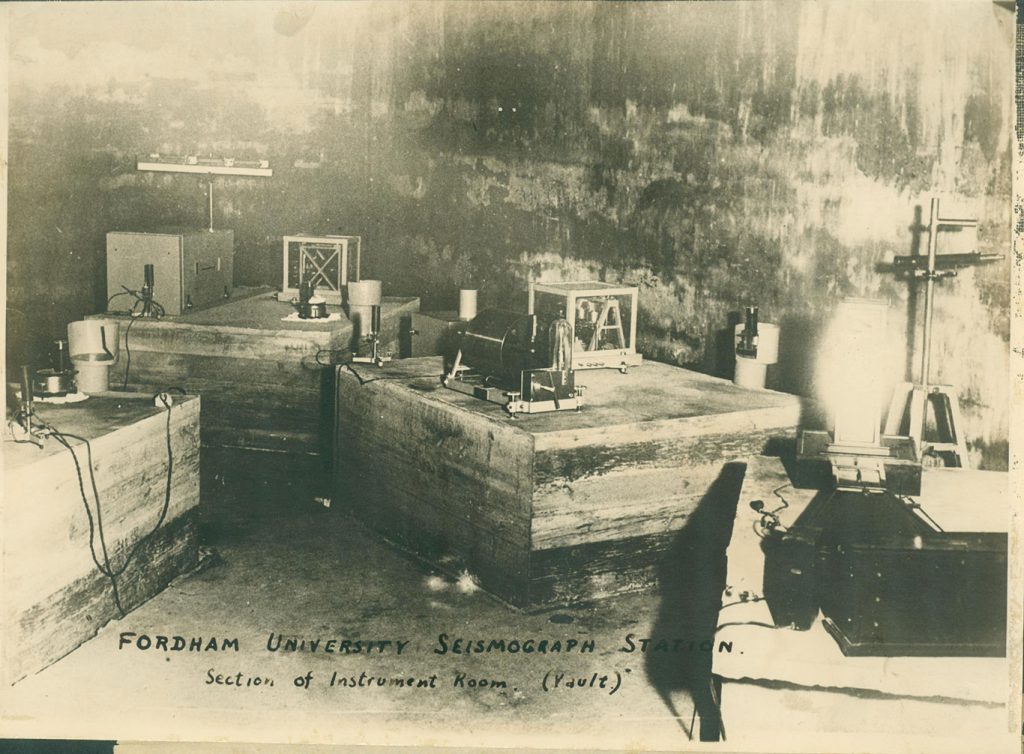

At the time, seismographs worked by utilizing a suspended mass—such as a weight—that remained relatively stationary, while the base of the instrument, which was fixed to the ground, moved during an earthquake. A recording of the relative motion between the mass and the base was recorded, providing a measurement of the ground shaking.

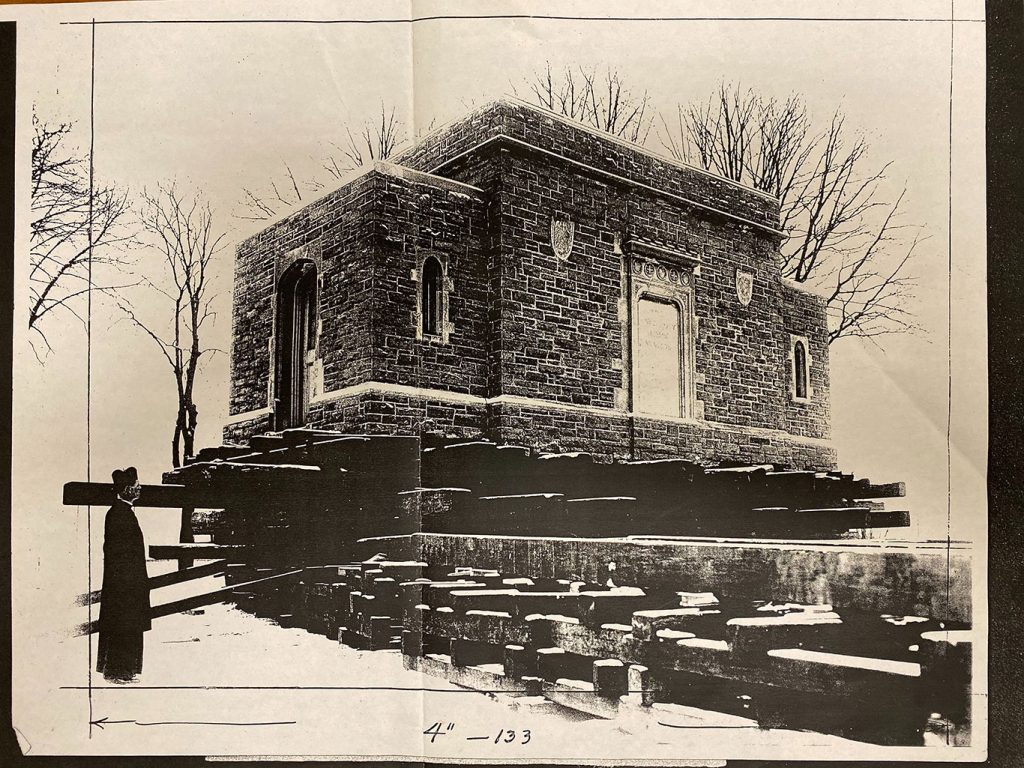

But the instruments worked best when isolated and in close contact with the bedrock. So in 1922, the University used stone acquired from a recent subway excavation to construct a building with underground space where they could operate with minimal disruption. It was originally built in the spot where Faber Hall now stands.

A Plaque From the Pope

Funding for the construction was provided by William Spain, whose son William, a physics student at Fordham, died that year. It was formally blessed by Bishop John Collins, S.J., Fordham’s 13th president, in a ceremony on Oct. 24, 1924. To honor the occasion, Pope Pius XI sent a bronze plaque with an image of St. Emidio, the divine protector against earthquakes, that is still embedded in the building’s exterior door.

In Pop Culture

Almost immediately after it opened, it became an object of fascination. A working model of the station was displayed at the 1939/1940 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, and Fordham displayed an operational seismograph at the 1964/1965 World’s Fair as well.

Father Lynch was routinely one of the first to report major seismic events around the world to media outlets. In April 1946, Life Magazine stated that the “Jesuit seismologist is America’s best-known interpreter of things that shake the earth, including milk trains, quakes, seismic waves.”

The station even became a part of pop culture. In a 1974 episode of the television show M*A*S*H. (starring Alan Alda, FCRH ’56), Colonel Henry Blake joked that he snores so loudly that he “even got a fan letter once from the seismograph people at Fordham.”

A Revival

In 1970, Father Lynch published a reflection titled Watching Our Trembling Earth for 50 Years (Fordham University Press), which recounted the ways he and fellow Jesuits worked together to perfect the science of seismology. Among other anecdotes, he noted how one night in 1929, in the course of calibrating the station’s clock with one at the Naval Observatory in Arlington, Virginia, he stumbled on bootleggers who were bottling whiskey on campus.

For several years after Father Lynch’s death in 1987, the station was either dormant or tended to by students who pursued seismology as a hobby.

In 1996, physics professor Ben Crooker took over supervision of the student club that had been using the equipment. By then, the field had changed a lot with the advent of the internet and increased computer power.

In 2001, thanks to a donation from an unidentified alumnus, Fordham was able to purchase a Guralp DM24 CMG3T machine, which combines the functions of a seismometer and digitizer. The University officially rejoined the international seismology community.

The Station Today

Today, measuring an earthquake now is akin to conducting a CT scan on the planet, with multiple stations—including Fordham’s—reporting observations from around the country to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) data repository in Boulder, Colorado.

“Fordham’s station is like one cell in a giant camera,” Crooker told Fordham News in 2007, “used to build a seismic map of the Earth.”

The Guralp, which looks like a coffee can with wires poking out of it, sits on a concrete pedestal beneath a plexiglass box and a blanket, which keeps it dust free and at a constant temperature. The data it collects is sent to a computer in Freeman Hall, which then relays it to USGS.

The rest of the vault is occupied by dormant equipment once used by Lynch and his successors. Every year on the day before commencement, Holler opens up the station to graduating physics students who marvel at the antiquated instruments.

“They’re kind of museum pieces, but they’re fantastic for quizzing the students on their physics fundamentals,” he said.