How do you know if a mouse is blind?

How do you know if a mouse is blind?

It’s hard to tell just by observing the mouse; unlike humans, mice rely less on vision and more on sense of smell and on their whiskers. (For those of you who know your nursery rhymes, this explains why Three Blind Mice ran after a farmer’s wife who was holding a kitchen knife.)

Yet a mouse’s eye photoreceptor rods and cones work very much like a human’s eye rods and cones.

Which is why Silvia Finnemann, Ph.D., associate professor of biology, measures and compares photoreceptor activity in live mice.

Finnemann’s work focuses on the causes of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), or loss of sight that accompanies the aging process. Of the 161 million people in the world who are visually impaired, 58 percent of them are over the age of 60.

Finnemann joined with research associate Ying Dun, Ph.D., and student-mentee Ramy Elattal (FCRH’ 10) on an experiment in her Larkin Hall laboratory to document the quality of vision in mutant lab mice that have reduced cellular anti-oxidant defenses, against normal “wild-type” mice. Anti-oxidants are molecules (found in green, leafy vegetables, pomegranates, etc.) that help prevent or reverse damage to living tissues caused by another type of molecule called a free radical. Free radicals (often formed when certain molecules interact with oxygen), have unpaired electrons, causing them to be very reactive with other molecules. When free radicals come in contact with DNA and cell membranes, the reactions damage them, a process called oxidative stress.

To test the eyes of live mice, the team uses an electroretingram (ERG) machine, which measures animal’s vision as well as human vision by means of simple electrical impulses detected on the surface of the eye by a contact lens—it’s a very similar procedure to an Electrocardiogram machine, which measures the heart.

An ERG can measure the light sensitivity of eye rods and cones and can also detect abnormal function in the retina. A healthy eye will respond to a flash of light much more vigorously than an unhealthy eye, so the team measured the different responses to light flashes in the two mouse groups, administering three separate recording sessions each with five consecutive responses at five different light intensities.

Those mutant mice that lacked proper anti-oxidant defense had a reduced reaction to the flashes of light, compared to the “wild-type” mice, whose response time was stronger and with larger amplitudes.

But the team wanted to see what the differences in the retinal photoreceptors of both teams of mice looked like as well. They used laser scanning confocal fluorescence microscopy, a process that takes pictures of a section of the retinal tissue.

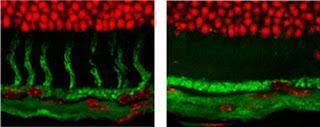

You can see the mice’s retinas in the laser photographs (left): an image of a cross-section of a mouse retina. The green color shows cone photoreceptor cells, and the red color is a DNA counter stain that shows where the different cell types in the retina are positioned.

You can see the mice’s retinas in the laser photographs (left): an image of a cross-section of a mouse retina. The green color shows cone photoreceptor cells, and the red color is a DNA counter stain that shows where the different cell types in the retina are positioned.

Now look at the following two photos. They offer a close-up comparison between a the healthy, normal mouse retina and a damaged retina in a mouse lacking antioxidant defense; the green squiggly lines in the wild-type photograph represent the presence of healthy cones.

Since there was no matrix of cones in the mutant mice, the scientists suggest that cones may be missing or defective and therefore impeding the vision.

Since there was no matrix of cones in the mutant mice, the scientists suggest that cones may be missing or defective and therefore impeding the vision.

So how does this relate to human blindness?

“Our cells and tissues have the same anti-oxidant defense systems as mouse cells,” said Finnemann, who studies cellular functions in the retina and their role in causing AMD. “But as this defense diminishes with age, our rods and cones malfunction.”

Finnemann said that identifying which components of the retinal cells are particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage is an important first step toward devising effective strategies how to prevent age-related blindness. Her other research includes a study (funded by the California Table Grape Commission) feeding mutant and wild-type mice a “healthy diet” enriched in grapes (good sources of anti-oxidants) and observing how this improves vision.

—Janet Sassi