A hyssop drink, a mugwort tea, a leek plaster applied to the skin.

For Kristin Uscinski, who is completing her doctorate in history this spring, these simple yet unusual mixtures can open doors into the lives of medieval women and their health care.

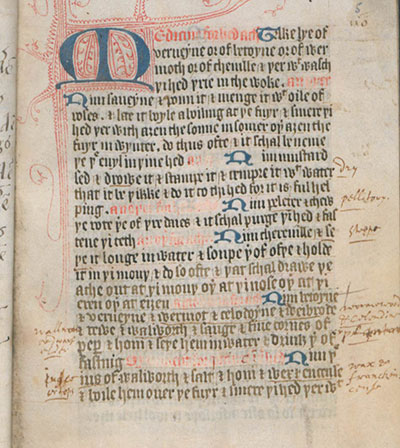

Uscinski has spent the last four years scouring through medieval medical recipe manuscripts, seeking to understand the major health complaints of women, the types of cures they sought, and how involved they were in their own healing practices.

The recipes she found revealed that medieval women were actively engaged in their own health care, both as professional practitioners and in their own homes, using botanicals that could be found in any domestic garden.

“From the beginning, when medicine is coming into its own as a profession in 12th-century Italy, women are there,” she said.

Supported by a Schallek Fellowship from the Medieval Academy of America and a Presidential Scholarship from Fordham, Uscinski travelled to England and studied more than 50 manuscripts, from the 12th through the early 16th centuries, at the British, Bodleian, and other libraries.

In order to fulfill her need for comparative and quantitative data, Uscinski used FileMaker Pro to create her own searchable database of about 2000 recipes.

The data she gathered showed that, not surprisingly, the most common complaints of women related to the reproductive system and childbirth.

What interested Uscinski, however, was how strongly her evidence pointed to women’s direct involvement in health care at home, making recipes in their own kitchens using techniques familiar to any cook.

“A lot of these recipes are very simple to make,” she said. “So if you can make tea and you can make soup, you can make these things.”

Charms, chants, and frog powder

Uscinski discovered that folkloric elements also made their way into the medical manuscripts— including charms, chants, and occasionally a frog powder or hare’s foot.

Though the effectiveness of the more eccentric recipes may be attributed to the placebo effect, she said, the other recipes appear to contain active ingredients more recognizable to a modern audience.

“When you see the same recipe 20 times there’s got to be a reason for it. I don’t think that they are just choosing these things at random,” she said.

She acknowledged, however, that testing the recipes is difficult, as there is no way to know if medieval ingredients correspond to the plants we know today.

Currently an adjunct professor of history at SUNY Purchase, Uscinski’s future plans include publishing her dissertation, which is titled Recipes for Women’s Healthcare in Medieval England.

Part of this work consists of her annotated transcription of a recipe collection called Isabella’s Book of Medicine, written for the wife of Edward II, which Uscinski would like to make more widely accessible.

She also hopes to put her searchable database online to help facilitate the work of others studying medieval medicine.

What motivates Uscinski’s ongoing work is her strong desire to help fill the gaps in medieval women’s history.

“Women can be remarkably difficult to see, especially in medieval sources, but they’re right there on the periphery. You have to look for them in a more creative way,” she said.

—Nina Heidig