If you’re feeling like deer are everywhere, you’re not wrong: their abundance in the Northeast has sparked widespread concerns, from the depletion of forests to highway accidents and more.

But any effort to address the problem faces hurdles—like pinning down the number of deer in different areas so land managers can decide whether to reduce the population, and by how much. Over the summer, Fordham teamed up with a conservation group to demonstrate a new counting method—one that involves cameras strapped to trees, snapping photos in unison throughout the day and night.

A Deer Cam That Takes Pics Like Clockwork

Researchers at a nature preserve called Mianus River Gorge, based in Bedford, New York, aimed to apply a new technique of photographing deer in order to get a more accurate idea of their numbers. Chris Nagy, Ph.D.—their director of research and education and a 2004 Fordham grad—proposed that the project be partly conducted at Fordham’s Louis Calder Center, which hosts student interns every summer in suburban Westchester County for 10 weeks of studying nature. One of this year’s interns, Fordham chemistry major Claire Renault, took on the project under Nagy’s mentorship.

Results: A More Accurate Count

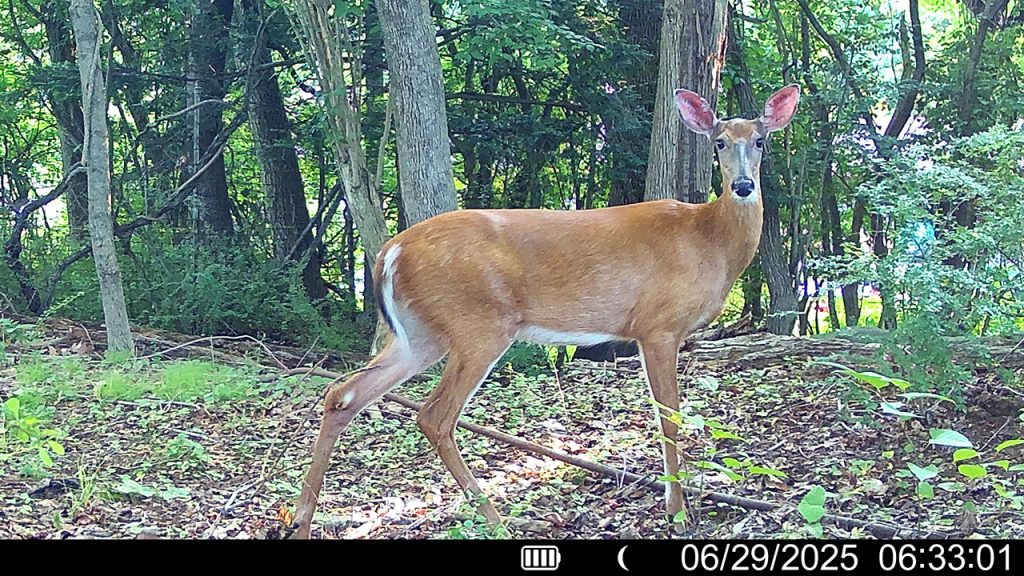

Over the summer, she gathered images from 10 cameras fastened to trees throughout the Calder Center grounds, which automatically took photos every 15 minutes at the same time for three weeks. The images show deer strolling across a clearing, catching some sun, or gazing into the camera.

As suspected, Renault found that the interval-based cameras captured deer that were missed by traditional motion-capture cameras, which she set up for the sake of comparison. Using the camera images, she calculated that there were approximately nine deer per square kilometer at Calder, slightly above the density of two to seven that’s optimal for healthy forest regeneration.

The Problems Posed by Too Many Deer

Deer overpopulation is an environmental problem for a few reasons, said the Calder Center’s director, Tom Daniels, Ph.D.: They feed on native plants, allowing invasive ones to take over; they consume acorns that might otherwise become trees that soak up carbon dioxide; and they provide a ready host for ticks, helping them proliferate.

Deer have multiplied because of the dropoff in bears and other natural predators. Also, as herbivores, they have abundant food, Daniels said. “We probably have more white-tailed deer now in this country than we ever had in our history,” he said.

Deer populations have been trimmed through hunting in the past, although some people have tried to give birth control drugs to deer—a method that hasn’t yet proved itself, said Daniels.

It’s important to get an accurate picture of the deer population for a particular area, since it may suggest that deer control isn’t needed, he said. To measure the population, researchers have been trying to track individual deer photographed by motion-capture cameras, but the deer can be hard to identify, sometimes leading to double counting, and their body heat doesn’t always trigger the cameras, Nagy said.

The new method gets around this problem with its photos that are snapped repeatedly, whether a deer is in front of the camera or not. Because the photos are simultaneous, every deer can be photographed only once at any given time, leading to more accurate numbers that can be used to calculate an areas’s estimated deer population.

Improved Tracking for the Future

The method was first proposed by then-University of Montana graduate student Anna Moeller and others in a 2018 paper. Nagy said his organization has tried this method in the past, but wanted to test it at multiple sites this summer that have varied terrain. In addition to her work at Calder, Renault helped with cameras placed at two Westchester County parks.

Renault said the new method should be further tested, perhaps by a longer study period. Over the summer, she helped refine and improve the study techniques that, Nagy said, are sure to be part of Mianus River Gorge’s toolbox in the years ahead.

“It’s just a better method, losing a lot of that uncertainty” that comes with trying to identify individual deer in photos, he said. Also, he said, “it saves us so much time and effort.”