“Marsh was a tireless advocate and activist for civil rights, rights for workers, worker-owned cooperatives, and social justice,” said John Davenport, Ph.D., a former director of Fordham’s Peace and Justice Studies program, which Marsh helped found. Davenport noted that Marsh was known for his defense of “critical modernism”—a form of critical theory that addresses postmodernist arguments by philosophers such as Jacques Derrida and Paul-Michel Foucault.

Born in Polson, Montana, Marsh earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington. He entered the Jesuit community there but left the order to pursue a Ph.D. at Northwestern University, which he earned in 1971.

From 1970 to 1985, he taught philosophy at St. Louis University. In 1980, he spent a year at Fordham as a visiting professor; five years later, he joined Fordham’s philosophy department full time. On his 20th anniversary in 2005, he was lauded with a Bene Merenti Medal, and was cited for thought that “fuses Marxist critical theory, phenomenology, process metaphysics and transcendental Thomism in critically constructive ways that counter the canon of modern secularism while issuing a sustained, sophisticated argument for social justice.” A year later, he retired from Fordham, his nephew T.J. Campbell said, and was named professor emeritus.

Over the course of his career, Marsh authored and co-edited nine books, including Post-Cartesian Meditations, (Fordham University Press, 1988); Critique, Action and Liberation (SUNY Press, 1994); Process, Praxis, and Transcendence (SUNY Press, 1999), and Unjust Legality: A Critique of Habermas’s Philosophy of Law, (Rowan and Littlefield, 2001). He was involved in numerous professional associations such as the American Catholic Philosophical Association, for which he served as president from 2004 to 2005.

Davenport said that when Marsh joined the Fordham philosophy faculty, he was part of a new generation of lay philosophers, along with Dominic Balestra, Ph.D., and Merold Westphal, Ph.D., to join what had been a department made up primarily of Jesuits.

“Marsh was seen as a new kind of thinker in the critical thinking tradition, but someone who respected transcendental Thomism, and therefore fit with into the department,” he said.

“What he called critical modernism was his own development of critical theory, which is a tradition of thought that goes back to the Frankfurt School in Germany just after World War II. It attempts to find new ways defending universal or objective standards.”

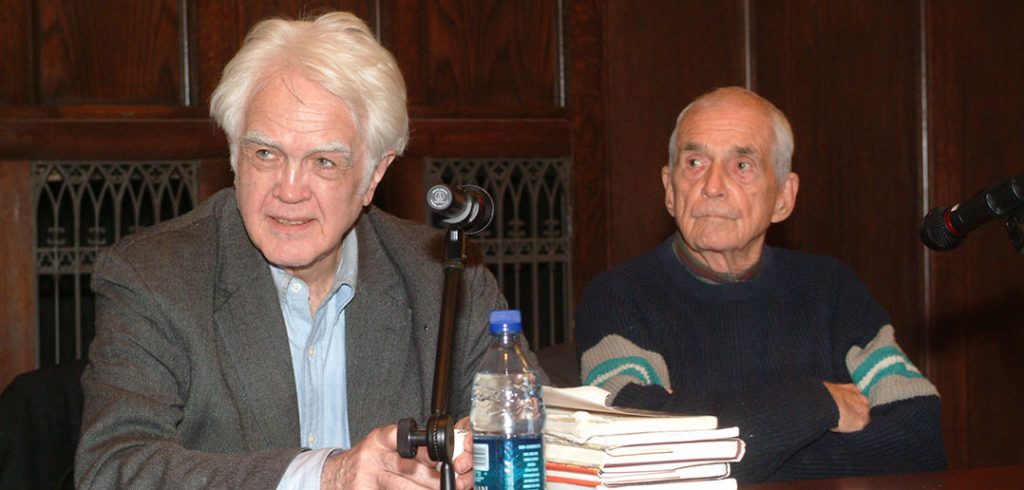

Davenport, who was on the faculty with Marsh from 1998 to 2006, said Marsh’s critiques of the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas had a big influence on him and his colleagues. A child of the Civil Rights era who was influenced by Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., Marsh was more open to theological themes and inspirations than Habermas. Marsh’s gift, said Davenport, was that he wielded those themes in ways that even non-believers could appreciate. He was also unfailingly polite to those who disagreed with him, he said.

“I think it’s fair to say he was a Marxist,” he said. “He wasn’t an activist professor though. I heard him say on more than one occasion that it was very important that students of all political persuasion felt free to debate openly. He really bent over backward to accommodate students of different political persuasions.”

Robin Andersen, Ph.D., a professor emerita of communications and former head of Peace and Justice Studies, hosted both Marsh and Berrigan for dinners at her home in New Rochelle. Because neither of them drove, she and her husband, Fordham lecturer of biology Guy Robinson, Ph.D., often found themselves in discussions with them on drives back to Manhattan.

“He was very committed in the classroom and the way that he would integrate his pedagogy in his teaching with the philosophy of aligning yourself to the poor. He would give the students a theoretical and analytical perspective about inequalities and global injustices, imbued with a philosophy about the nature of human lives, and how we all need to live with dignity,” she said.

Marsh was a dedicated pacifist and used The Trial of the Catonsville Nine (Fordham University Press, 2004), in his classes. The book, which details Berrigan’s trial for civil disobedience at the height of the Vietnam War, features afterward by Marsh and Andersen.

Andersen said she’ll miss Marsh’s thoughtfulness and the ease with which he engaged in conversation.

“Some very thoughtful people can be kind of intense, and Jim didn’t have that intensity about him,” she said.

“Both Dan [Berrigan] and Jim were very much into creating community around them. They had a real commitment to bringing young people into a world that is not easy to find in our culture, one filled with thought, compassion, and deep contemplation about what we’re doing in our fast-paced professional world,” she said.

Campbell said that he and his sister Elizabeth Campbell, Ph.D., benefited tremendously from time spent with their uncle, especially through holiday visits to Colorado, where Elizabeth lives and teaches at the University of Denver. Their education began with books on artists he bought them when they were children and continued through the years.

“Jim had an enormous influence on Elizabeth and me from a young age, particularly in terms of our appreciation for modern art and dance and theater,” he said noting that he exposed them to Twyla Tharp’s In The Upper Room, which combined several forms of art, including music by Philip Glass, one of Marsh’s favorite musicians.

Marsh was a devoted fan of the UConn women’s basketball team and subscribed to the Hartford Courant newspaper so he could keep up with them, Campbell said. He also devoted two hours a day to centering prayer, a form of meditation where one focuses on a single word such as light or love.

During one of their last visits to Colorado for Thanksgiving, Campbell said that Marsh confided to him that being a bachelor was also an important part of his identity. Despite a penchant for living alone, Marsh nonetheless drew others to him, he said, with a keen intellect, deep insights into modern culture, and a big booming baritone voice.

“His students loved him, and his friends and colleagues loved him as well. When we were at museums, he would comment on a painting, and people gathered around to listen to his commentary like he was a docent,” he said.

“He was so knowledgeable about the artists and how the paintings were constructed, that people would follow along with us.”

In addition to T.J. and Elizabeth Campbell, Marsh is survived by his sister Mary Ann Courtney and grand-nephews Ryan and Grant Karlsgodt. A funeral Mass will be held for him at St. Francis Xavier Church, 46 W. 16th Street, on Friday, Sep. 24, at 10:30 a.m. All are welcome.