“African and African American Studies is not merely for Africans or African Americans; African and African American studies are American studies, studies of who we are, who we wish to become,” said Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham. “It is, I think, a great sin for people who really don’t want to listen to what the African American experience can and must tell us … We have much to learn and much to celebrate.”

Organized by Amir Idris, Ph.D., professor and chair of African and African American Studies, the day began with a panel of founding faculty members who discussed the challenges they faced forming the department in the early days amidst national strife. A group of Bronx African community members later testified to how research conducted by a Fordham professor has helped bring much-needed services to their community. Another panel on emerging scholars on Africa and the African diaspora from across the University debriefed the crowd on their latest research. And Farah Jasmine Griffin, Ph.D., chair of Columbia University’s newly formed African American and African Diaspora Studies, took a comprehensive look at the current challenges and hopes for the future.

By day’s end, Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African and African American Studies, the longest active member of the Department, who joined its faculty in fall 1970, was deeply moved by the panels’ trajectory. He spoke of the value research can have on communities of color.

“It really makes you realize what we’re doing matters,” he said. “It makes a difference.”

Hurdles of Coming into Being

Moderated by Naison, the first panel featured the department’s founding faculty talking about incidents that are fairly well known in the University community, such as the student protests that led to the formation of the department at Rose Hill, when nearly a dozen African-American students refused to leave the office of dean of student affairs until an agreement was reached to create an African American studies curriculum.

Perhaps less known was the concurrent development of the department at the Lincoln Center campus. Three faculty from Fordham College at Lincoln Center (FCLC), Irma Watkins-Owens, Ph.D.; Fawzia Mustafa, Ph.D.; and Selwyn Cudjoe, Ph.D., recalled a department that had to make its way with little funding at the then-brand-new campus.

Cudjoe said it was a student movement that brought black studies to FCLC, adding that students were also very involved in the hiring of the faculty and selecting the courses. He said offerings were limited and students were recruited from Harlem, Bedford Stuyvesant, and the Bronx.

“There was no blueprint for building and sustaining a department like this,” he said.

Mustafa recalled that the formation of the FCLC department took place well before the restructuring that wove together faculty from the two campuses. Not only was the FCLC faculty autonomous from Rose Hill, but the African American studies department was less integrated with more established disciplines at FCLC as well. Resources were thin. Grant writing and fundraising became the only ways to bring some of the great black thinkers to campus. Watkins-Owens recalled relying on the library’s budget to build up the resources on African and African American content—a move that prompted an appreciative thank you note from the librarian for filling in a major gap in the collection. Watkins-Owens concurred with Father McShane on the importance of African American scholarship to all students.

“Black studies are for everyone, although some might try to lessen its importance in the current political climate,” she said.

Watkins-Owens said there is cause for concern for the discipline’s future, which may be reflective of overarching concerns for the survival of the liberal arts generally. She noted that there were more than 600 African American history programs in 2013 and that number has dipped to 361 programs nationwide. She urged “caution, vigilance, and activism.”

Research Affecting Communities

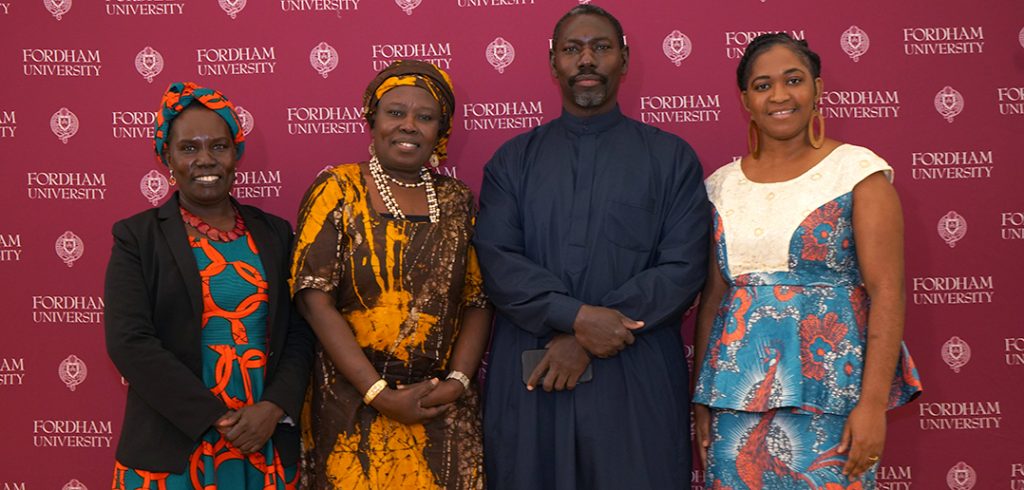

During a panel session with African community leaders from the Bronx, Sudanese native Jane Edward, Ph.D., clinical associate professor, moderated a discussion on how research could be used to help communities, not merely help researchers.

In 2006, Edward joined the Bronx African American History Project to engage the growing community. She and Naison went to events, schools, and organizations, eventually gaining trust. An ethnographer by training, she compiled a list of African establishments that contribute to the vitality of the city, including 19 mosques, 15 churches, 20 businesses, 19 markets, nine restaurants, six hair-braiding salons, six newspapers, four community organizations, two law firms, a women’s organization, a research institute, and a website.

Activist and community leader Ramatu Ahmet recalled how researchers often use her community to grab statements and data then never return to show them the results. Edward returned, again and again, to update the community on her progress, Ahmet said.

Christelle Onwu, a recruitment strategist with the New York City Commission on Human Rights, said that her background in social work helped her appreciate that little can happen on a policy level without good data, which she said Edwards’ paper, “White Paper on African Immigration to the Bronx,” provides.

“To convince an official you need to have numbers,” Onwu said.

“It is very difficult to make change without knowing what the needs are,” she said, noting the importance of research. But, she also warned, “It’s important that [researchers’] subjects don’t feel used, abused, or traumatized.”

To the Future

A forward-looking conversation among emerging scholars of the African diaspora prompted panelist Lauri Lambert, Ph.D., assistant professor of African and African American Studies, to state that she looked forward to when her fellow panelists will be referred to as “established scholars.” It was a fitting precursor to a keynote address delivered by Farah Jasmine Griffin, Ph.D., which examined the current state of the discipline, as well as the outlook for its future.

But first, she started by thanking Fordham for its past and expanded on other significant anniversaries that took place this year, including the 400th anniversary of the 1619 arrival of Africans in the Americas that laid the foundation for slavery in what would become the United States. She noted that while many of the year’s anniversaries were worth commemorating, Fordham’s was worth celebrating.

“This department represents the very best in the tradition of black studies, which through intellectual rigor and its commitment to social justice, seeks to do no less than transform the world,” she said. “And given that you all are one of the oldest and most successful departments you’ve served as inspiration for us at Columbia … [though]we are half a century late.”

She noted that she has been inspired by the work of early Fordham faculty, including writings by Watkins-Owens and Naison. She said that scholarship produced nationwide by African studies has enhanced traditional academic disciplines, especially history, anthropology, sociology. As she looked to the future she cited three sites of engagement for the discipline: in the classroom, in the world, and on the planet.

In focusing on the classroom, she spoke of a variety of contemporary theoretical perspectives including Afro-pessimism (how anti-black violence influences society), Afrofuturism (an Afrocentric intersection of science, history, and technology with utopian visions for the future), black feminism, black queer studies, and black performance studies.

“Now these are oversimplifications of these very rich and complex theories meant only to underscore their robust contribution to the original analyses of black life, culture, history, and the blessed nations,” she said after briefly explaining the theories. “Afrofuturism has been especially attractive to practitioners in technoculture, readers, and writers of science fiction, and some pop culture artists like Janelle Monáe,” she said.

And while she praised the new perspectives and the excitement they bring to students, she also raised concerns that they turn attention away from the dominant continental/European theories that can also serve to frame modern understandings of black life.

“One of the limitations [of the new theories]is the way that such students seem to strongly feel that there is little value outside what this body of work has to offer, resulting in, at best, a failure to appreciate earlier work or, at worst, a dismissal of it as theoretical or old fashioned,” she said.

In the speaking of the world perspective, she noted that few from the discipline were naive about racial progress expected after the election of Barack Obama.

“Nonetheless, in spite of this awareness, few of us, myself included, were prepared for the extent to which the pendulum swung backward in this nation,” she said. “The rise of right-wing, populist nationalism; naked white supremacy; and neo-fascism throughout the Americas, Europe, and Asia has been especially striking.”

When she focused on the planet and the role of Africana studies, she noted that climate change inordinately affects low-income communities of color around the world. She said too few lessons were learned from Hurricane Katrina, as thousands in Puerto Rico and the Bahamas remain devastated from storms there.

She called for a “greening” of Africana studies. “We need more work on the impact of climate change on poor communities and on Island nations, particularly in the Caribbean. And furthermore, we might explore ways that our own institutions can work with these communities on these urgent issues.”

Capping with Culture

While the majority of the day was filled with thoughtful dialogue, the panels and lectures were buttressed by performances of African percussion, singing, and dance by performers from Broadway’s The Lion King. During dinner, one could hear discussions about Muddy Waters coming from one table to Toni Morrison at another and Henry Louis Gates at a third. By the time the cake arrived, DJ Charlie “Hustle” Johnson had pumped up the music to bring the crowd to the floor. The evening was capped by a rap performance by Dayne Carter, FCRH ’15.