Some institutions define people’s lives forever. In the case of Robert O’Brien and his wife Astrid, that institution was Fordham.

Robert O’Brien, FCRH ’53, GSAS ‘65, associate professor of philosophy emeritus, died last month from COVID-19 complications at age 88. He left behind a life story in which Fordham touched every role, from student to teacher to husband to father.

Raised in Queens, O’Brien enrolled at Fordham in 1949 through a city scholarship and developed an interest in modern philosophy, choosing it as a major. In 1959, the young doctoral student was hired full-time to teach philosophy at Fordham’s Manhattan campus, then located at 302 Broadway.

According to O’Brien’s daughter Carol Haagensen, FCLC ’95, a Jesuit priest played matchmaker when Fordham hired a young female adjunct professor, Astrid Marie Ritchie, the same year.

“Here was this nice, single woman, and the Jesuit thought, what the heck? My father was of marriageable age … so he assigned them to share a desk,” Haagensen said.

O’Brien and Ritchie both taught evening classes. When the two professors would finish teaching for the night, O’Brien, who lived in Jackson Heights, Queens, would drive Ritchie home to Staten Island.

“One of my mom’s friends told her, ‘You know, nobody drives you all the way to Staten Island unless he’s very interested in you.’ I think that gave my mom a nudge,” said Haagensen.

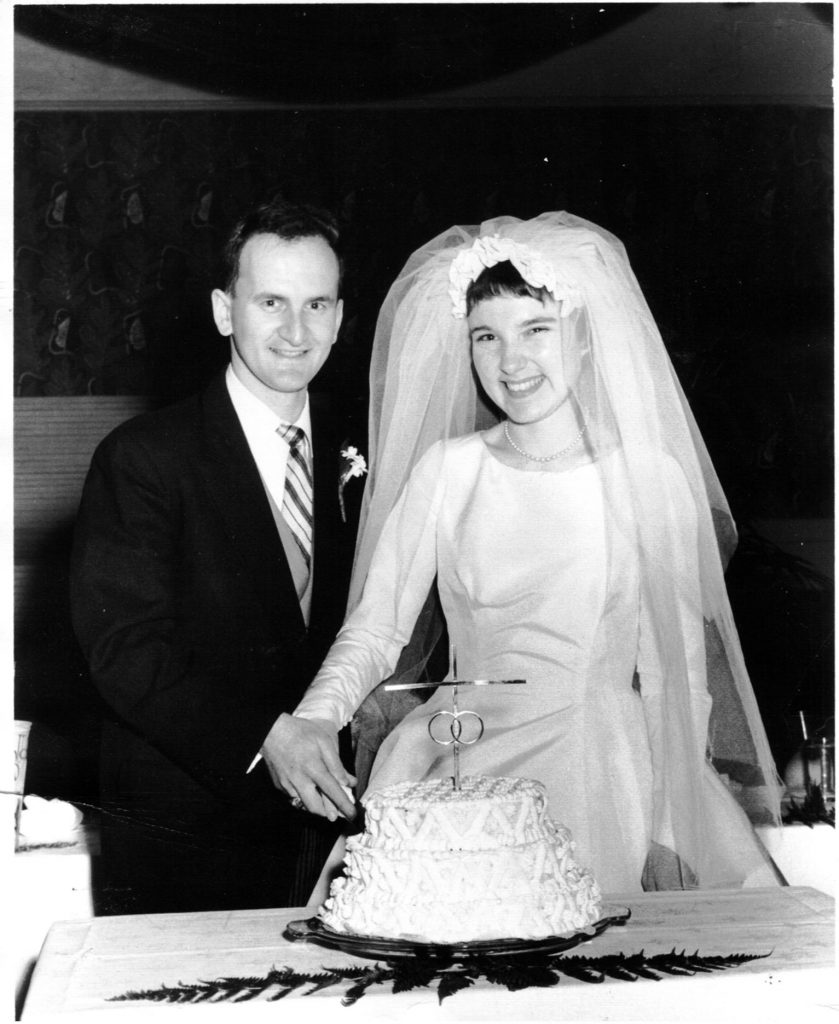

The couple married in 1960. According to an article in the Fordham Observer, then-University President Laurence McGinley, S.J., sent them a $100 gift. With it, they purchased a desk on which they wrote their dissertations.

The O’Briens’ teaching careers at Fordham spanned more than 50 years. Those who worked with them said they were essential figures in Fordham College at Lincoln Center’s (FCLC) philosophy department.

When they started teaching, said Dean Emeritus of FCLC Robert Grimes, S.J., philosophy was not part of a core curriculum like it is today. Students had the option of taking either one philosophy or one theology course to complete the degree requirement.

“They had to convince students to take philosophy, and they proved their worth to students successfully for many years,” he said.

In addition to his full teaching schedule, O’Brien also worked as an assistant dean, performing well beyond the dictates of the two positions, Father Grimes said. In the 1980s, he added, O’Brien started a student research journal “long before the idea of student research became popular everywhere.”

“The journal was so much ahead of its time. He recognized the talent in students and wanted to encourage it. He was tremendously devoted to the good of the college.”

Colleagues recall O’Brien and his wife as people of deep Catholic faith who regularly attended Mass at the Lincoln Center campus. As part of his assistant dean’s role, O’Brien had to make up the campus’s academic calendar each year, said Leonard Nissim, Ph.D., an assistant professor of mathematics who retired in 2016. Nissim recalled pointing out to O’Brien that there are 14 possible mathematical combinations for any annual calendar; why didn’t O’Brien just do the 14 and reuse them?

“And Bob looked at me and said, ‘You forgot Easter. Easter changes every year, and it’s the most important day.’ And Bob was right. Easter’s date depends on the Vernal Equinox and full moon, not a calendar.

“Bob was a trifecta. Well-liked by deans, faculty, and students,” he added.

John Davenport, Ph.D., professor of philosophy, said O’Brien encouraged him when he was struggling to find his way as a new professor with a young family. O’Brien invited Davenport to teach modern philosophy even though it was a topic he loved to teach himself.

“His support was a great help to me in my first two years,” said Davenport. “He was a gem of a human being [and]I feel eternally grateful to him,” he said.

Although O’Brien was a scholar of modern philosophers such as René Descartes and Baruch Spinoza, his interest included other areas of philosophy, said Haagensen. He had a fascination for 19th-century transcendentalism, particularly the works of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Bronson Alcott. Haagensen recalled her father taking her on a trip to Walden Pond.

“It was home-grown American,” she said. “And it was a nice way to make you realize that there were flesh-and-blood people who came up with these ideas.”

O’Brien retired from full-time teaching in 2009, but he continued to teach in Fordham’s College at 60 program. In 2010, after 50 years of marriage, he and Astrid renewed their wedding vows in Fordham’s Lincoln Center chapel among friends and family.

When Astrid passed away in 2016, said the couple’s daughter Frances O’Brien, FCLC ’86, her father was deeply moved by the University’s recognition of her.

“Fordham was very much the center of my parents’ lives,” she said, “and a source of great pride for them both.”

Besides his two daughters, O’Brien is survived by a son, Robert J. O’Brien, and three grandchildren. A memorial service is on hold, said Frances O’Brien, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“When life gets back to normal, we can honor him with the kind of service he deserves,” she said.

—Janet Faller Sassi, GSAS ’10