The fascist regime of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco lasted 40 years. But when he died in 1975, it crumbled with remarkable speed, and three years later Spain emerged as a democracy.

According to Louie Dean Valencia García, it was no coincidence that the system there has stood the test of time since 1978—even as countries such as Iraq and Egypt have foundered in their attempts at democracy. What he found was that the Spanish people had been “creating pluralistic or democratic spaces even in the 1960s.”

“[Democracy] was something that was already happening,” said Valencia García, who today is earning a doctorate in history from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. “Franco’s death just allowed for it to be done more so in the open.”

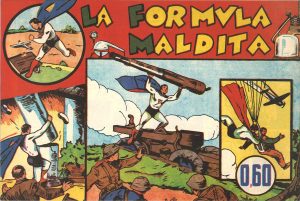

Beyond the tightly controlled media and textbooks of the Franco era, the youth were imagining a better world through comic books, said Valencia García. As part of his doctoral research, he traveled to Spain on grants from the Spanish national government, Santander University, and the U.S. Library of Congress to see notes that Franco’s censors attached to copies of Superman comics. He published his findings in his dissertation, Making a Scene: Comic Books, Punk Rock, Antiauthoritarian Youth Culture, and Creating Democratic Spaces in Franco’s Spain, 1955-1984.

“Lois Lane was a woman who had a job, wore pants, and told Superman what to do, and Superman was dangerous because he had a double identity,” said Valencia García. “He often rejected Lois Lane’s advancements and was represented as an asexual character, so he was queer in some way.”

“Fascism is about masculinity. It’s about women producing for the country. So men who bow down to women and who are not necessarily adhering to the norms of the dictatorship, and women who are also transgressing them―these behaviors are anti-fascist.”

Valencia García has been reading comic books regularly since he was 11, thanks in part to his mother, who took him to the store every week and who never imagined he’d continue to read them as an adult. He credits the late Christopher Schmidt-Nowara, Magis Distinguished Professor of History at Fordham and his adviser, for encouraging him to research them for his dissertation.

“People will say, ‘You study comic books? That’s a little weird.’ But it’s studying questions about mass production, technology, capitalism, and American culture abroad that’s operating under a dictatorship,” he said, “and what it means to be a young person in a global society.”

Indeed, if it’s a trivial topic, Harvard University missed the message. In July, Valencia García will begin a three-year term as lecturer in the school’s department of history and literature. He’ll teach one or two classes a semester of his own design (he’s leaning toward a class about graphic novels in the 20th century in Europe) to about 10 students. He’ll also mentor two to three students who have an interest in youth culture movements like Occupy Wall Street.

“It gives me time to do research and gives me time to turn my dissertation into a book,” said Valencia García, to whom Fordham has been a supportive home for seven years. “It’s phenomenal.”

When Schmidt-Nowara (who’d moved on to Tufts University but still remained Valencia Garcia’s adviser) died suddenly in 2015, Valencia García said he was overwhelmed by the support he received from all corners of the University. History professor and chair of the urban studies program Rosemary Wakeman, PhD, stepped in to replace Schmidt-Nowara as Valencia García’s adviser.

“Literally everybody in the history department backed me up immediately, and they’ve been there the whole time,” he said.