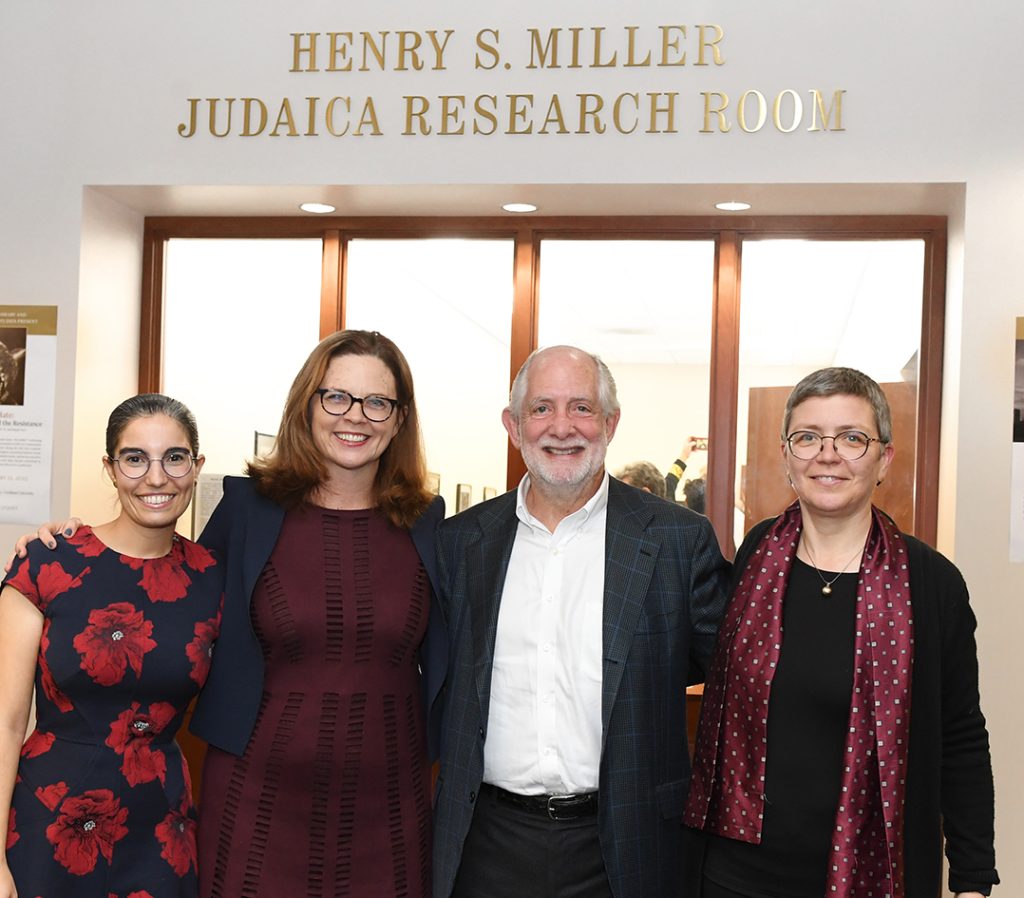

It was an unexpectedly emotional affair on the fourth floor of the Walsh Library when faculty, students, staff, and friends of Fordham’s Center for Jewish Studies gathered to inaugurate the Henry S. Miller Judaica Research Room and celebrate the center’s fifth anniversary on Oct. 20.

The new research room will be a space for future art exhibitions and will serve as a seminar room for small talks and presentations once the proper technology is installed.

Miller, who graduated from Fordham College at Rose Hill in 1968 and is a University trustee, said he had a very positive experience with Jesuit education as a Jewish student.

“I was a poor Jewish kid from Liberty, New York, and Fordham provided financial aid that allowed me to attend college,” said Miller, who has been a great supporter of the center since its inception. “I had a lot of Catholic friends and neighbors, so I wasn’t intimidated by the atmosphere of a Jesuit campus.”

He said he got a great education and became a believer in Jesuit education, particularly the “concept of cura personalis and teaching students how to think.” He has always found the Jesuit approach to theology and philosophy to be inclusive and open-minded, he said, though up until recently, there was nothing resembling the Jewish Studies program at Fordham. He tipped his hat to Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president emeritus of Fordham, and “our Jewish provost [the late]Stephen Freedman, a blessed memory” for supporting the inception of the center along with Eugene Shvidler, GABELLI ’92. Shvidler endowed a chair in Judaic studies held by the center’s co-director Magda Teter, Ph.D. Sarit Kattan Gribetz, Ph.D., also co-director of the center, acted as the evening’s host.

“In a very short time—especially by university standards—Magda’s insight and hard work have created a fantastic program that stands out for its bold approach,” Miller said.

He added that antisemitism has become rampant on campuses throughout the world, underscoring the need for a program that “bridges cultures, religions, and even races to help everyone gain understanding.” It’s what made him want to give to the program in the Jewish tradition of tikkun olam, often translated as “repair the world,” which he said is perhaps best embodied in a poem by Alberto Ríos.

“We give because someone gave to us. We give because nobody gave to us,” Miller said, quoting the poem, before being overcome with emotion on reading the next line. “We give because giving has changed us. We give because giving could have changed us.”

Miller was followed by Tania Tetlow, president of Fordham, who described herself jokingly as “a wannabe Jew” and told the crowd of her time singing in the choir of a New Orleans synagogue. She said she had not missed the high holy days for 20 years.

“I’ve understood how deeply intertwined Judaism and Catholicism are… and the connections we have of the deep intellectualism of both faiths, of the desire to study text and the interpretation of text going back for thousands of years, of the love of ritual,” she said, before adding to much laughter, “and the central place of food and guilt.”

To mark the occasion, a photo exhibition was hung in the research room; it’s titled “Jewish Remnants in the Bronx: Photographs by Julian Voloj.” At the reception, Voloj’s black and white contemporary photos, a few of which portrayed a layered history of Pentecostal churches housed in old synagogues, were hung above tables displaying a local Jewish family’s photos and records that were culled from the library’s archives and curated by Jewish studies minor Reyna Stovall, a sophomore at Fordham College at Lincoln Center. She said that working on the exhibit helped her appreciate the Bronx and its history.

“History teaches us so much about life and troubles and prosperity,” said Stovall. “History can teach us so much about not only the past, but about ourselves, and the future we want to create.

Following the program, Rabbi Yigal Sklarin of the Yeshiva of Flatbush offered a blessing for the room. Miller hung a mezuzah on the doorframe of the room that now bears his name.

“The mezuzah highlights the ability of the individual to sanctify the private spaces we inhabit: a belief in the capability of the individual to elevate their surroundings and uniquely infuse them with holiness and meaning,” said Rabbi Sklarin. “But the mezuzah also serves as a reminder as we leave the private and emerge into the public sphere. It is our role to take this holiness and meaning and share it with the world at large.”