Just after the inauguration ceremony for President Tania Tetlow in October, revelers gathered in front of Walsh Family Library—aglow in purple and blue lights—to boogie down to the sounds of the famed Preservation Hall Jazz Band.

It was hard to imagine that in 1994, this was just an empty patch of land, and not a five-story, 240,000 square-foot anchor of the Rose Hill campus’ southwest corner.

This year, the library is celebrating the 25th anniversary of the day it opened its doors to the Fordham community.

The Paradox of Libraries

For Linda LoSchiavo, TMC ’72, director of Fordham Libraries, the anniversary has been an occasion for reflections on the library’s ultimate mission. She noted that libraries have always been a bit of a paradox, and Fordham’s is no exception.

“On the one hand, it’s perceived as somewhat of a cloister. It’s a place of quiet study and meditation. It’s kind of a retreat from the clamor of the world,” she said.

“But in fact, we’re also functional. Every day, the doors open, and the University enters. We’ve got students coming in. They might work alone, but they also form communities, they make connections, and all the learning is shared. So, we have to fulfill those two functions.”

‘Cathedral for the Curious’

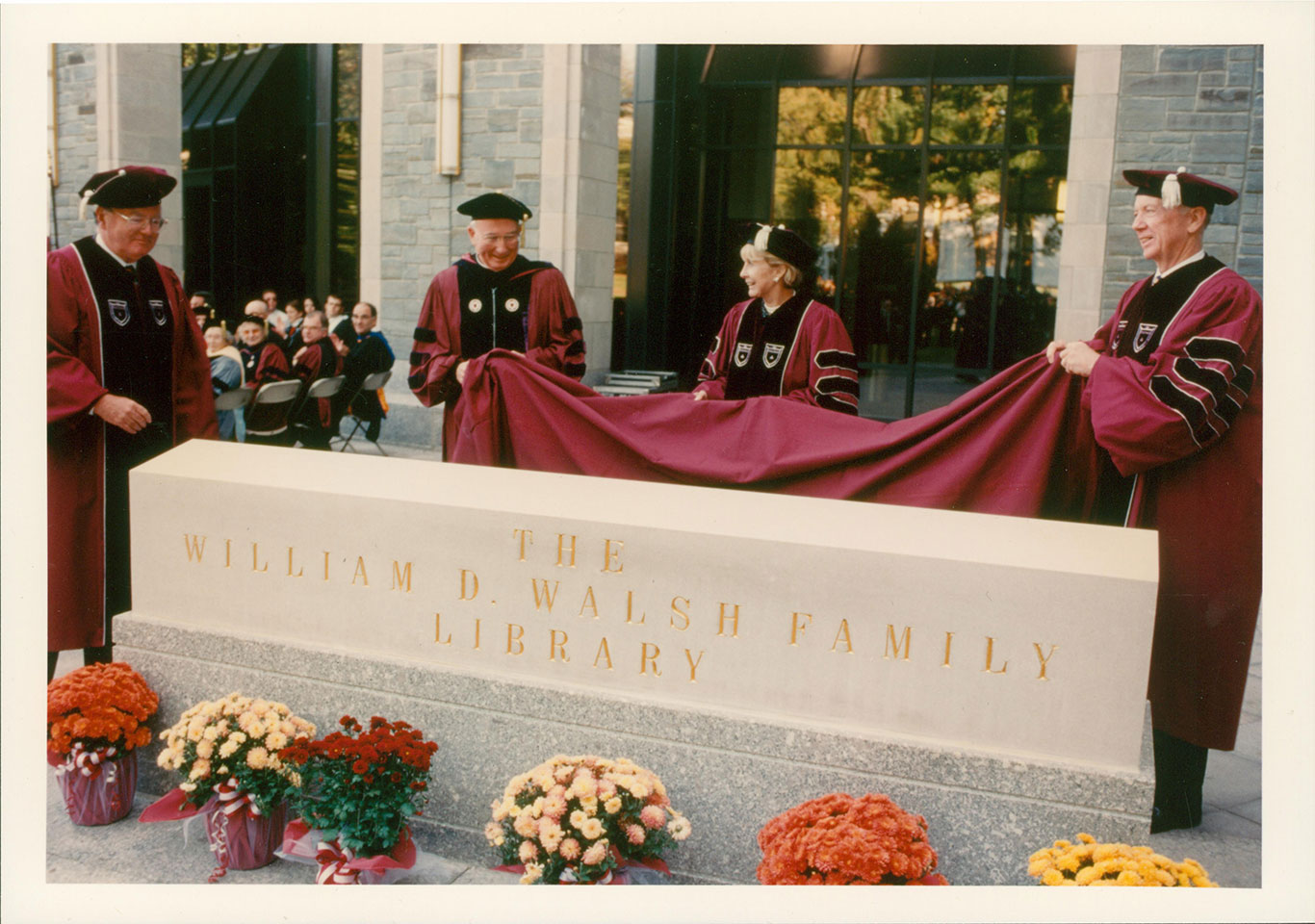

The William D. Walsh Family Library opening ceremony took place on October 17, 1997, after just under three years of construction. It cost $54 million, $10.5 million of which came from William D. Walsh, FCRH ’51.

Joseph O’Hare, S.J., Fordham’s president at the time, presided over the ceremony. He was joined by John Cardinal O’Connor, who hailed the structure as “one of the most enriching facilities that at least I have seen since I have been Archbishop of New York.”

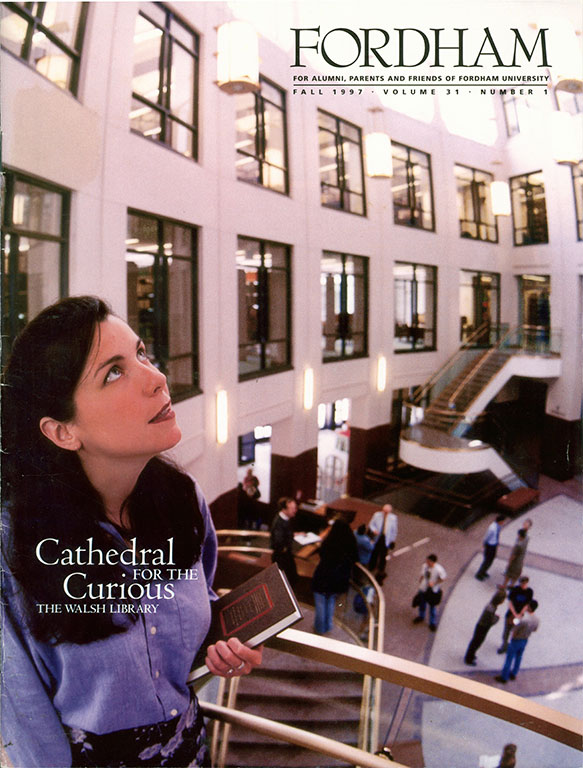

That fall, Fordham Magazine’s September issue was devoted to the new library, which it dubbed the “Cathedral for the Curious.” O’Hare said it successfully integrated with the Neo-Gothic architecture of the campus’ signature buildings, yet was contemporary in its look.

“[It is] not a stone fortress, but rather a window of welcome of the University’s life of learnings,” he wrote in the magazine’s introduction.

The new building was high-tech for its time, housing 350 computers, video equipment, and study carrels quipped for laptop use. Resources were also shared beyond the Fordham community; with help from a New York state grant, a new technology center provided software training and teachers in the Bronx and lower Westchester.

An Operation Scattered Around Rose Hill

When Walsh Library opened, LoSchiavo did not work there, as she was director of Quinn Library at Lincoln Center at the time. But she had worked at the Rose Hill campus in the years before it was completed. When she joined Fordham in 1975, the University had long outgrown Duane Library, which opened in 1926 with just 31,500 square feet of space and seating for 504 patrons. As a result, library operations were scattered among five different buildings. Chemistry, biology, and physics books were stored in three separate locations before they were combined into one science library in 1968, when John Mulcahy Hall opened. And the library’s cataloguing and acquisitions departments shared space with the periodicals collection in the basement of Keating Hall, where LoSchiavo worked for a time.

When Walsh opened its doors, it not only eliminated inefficiencies that came from being spread out, she said, it also showed how the right space makes it possible for a library to evolve to meet the needs of its patrons.

In fact, she noted that shortly after it opened, administrators realized that the first-floor periodicals reading room, where physical copies of journals and magazines sat neatly arrayed on shelves, had been rendered obsolete by electronic publishing. Less than a year later, the space was transformed into the Museum of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Art.

Designed for Change

LoSchiavo called the changes, which have taken place in innumerable instances small and large throughout the building, are the result of “controlled flexibility” inherent in the blueprints drawn up by the building’s architect, Shepley Bulfinch.

Photocopier rooms? Those have become group study rooms. Offices for other divisions around the university? Three of them were combined into one unified space now occupied by a writing center. This summer, a section of the basement that was once storage for printed copies of dissertations was transformed into the Learning & Innovative Technology Environment (LITE) center. Last month, a fourth-floor reference desk that was a holdover from the separate science library was christened the Henry S. Miller Judaica Research Room.

It’s all part of the push and pull of simultaneously preserving the past while promoting the future.

“When you look at stacks, what you’re seeing is immortality. And then you get these students coming in—and they can be loud, but they’re vibrant. And there’s your future right there, coming through the door,” she said.

“When we opened the lower level, we had an electronic information center, which at the time, oh my God, was that revolutionary. We had all these computers and computerized databases. But now, the term electronic information center is really dated. I mean, the whole building is an electronic information center.”

A Centerpiece for Sustainability

Not all the changes to the building have come from shifting research and studying habits. Given its size and its hours of operation, the library is also the biggest energy user on campus, and is thus a centerpiece of Fordham’s sustainability efforts. In 2010, it became the site of the University’s first solar panel array, and in 2019, clean energy servers installed there helped Fordham offset more than 300 metric tons of carbon dioxide each year.

As the University continues with efforts to reduce its carbon footprint by 40% by 2030, Walsh Library will stay in the spotlight; this year it will be the first building to undergo an energy audit to determine what can be done to further shrink its energy consumption.

For LoSchiavo, it’s all part of the job.

“It used to be that people felt that things changed very slowly in libraries, but as a matter of fact, they don’t. They actually change on the rapid side, and it’s actually hard for us sometimes to keep up with the new ways that things are being delivered,” said LoSchiavo, whose team celebrated the building’s silver anniversary by creating Walsh25, a campaign featuring a resource guide, giveaways, displays, and blog postings.

“But what we’ve found over 25 years is that students still need information. The faculty still need information. They still need a place to study. They still need a place to read. They need a place to do research. They need a place to collaborate with one another. They still need the librarians to guide them through the process.”

Photo by Patrick Verel